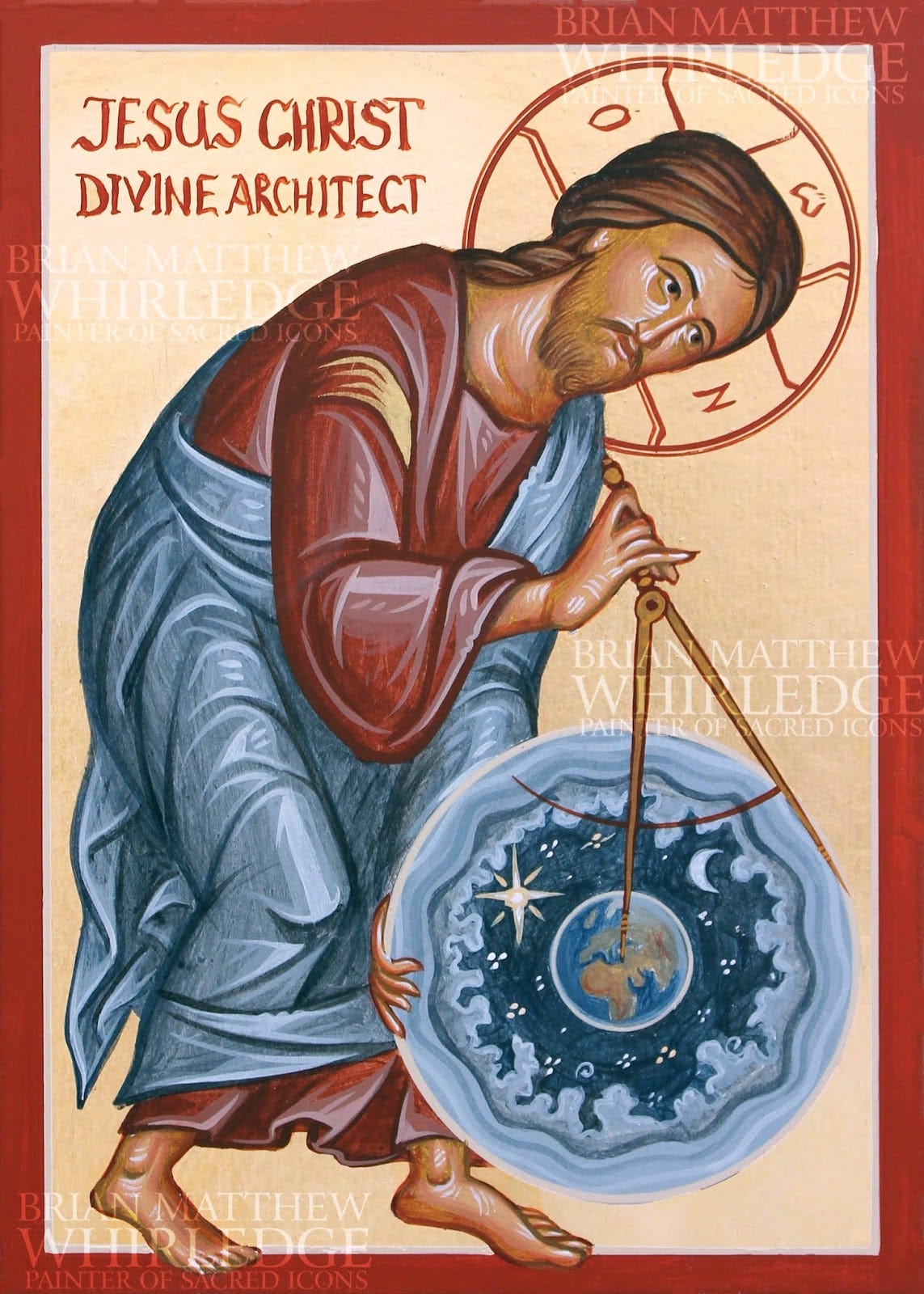

The Archdiocese of Regina in Saskatchewan, Canada recently published a theological article which I wrote. That article is entitled “Eternally Begotten: The Man Who Created the World.” There was a comment on the article, asking:

What makes something begotten vs. created?

You can read the original article here, but it’s not necessary to read it. Thank you to Aaron on YouTube for asking such a great question.

What makes something begotten vs. created?

The Greek word from which we translate ‘begotten,’ is monogenēs. That Greek word means “being the only one of its kind within a specific relationship,” and/or “being the only one of its kind or class, unique in kind.” So with the “only begotten Son,” or “eternally begotten,” we are talking about a specific kind of identity relationship—unique to the Father and the Son.

But in general, on the human scale, and with the Father and Son, begetting is about a transference of essence. Creating might make something in the same image, but the created thing is not of the same essence as its creator.

Saint Athanasius insists that Christ is of the same substance, meaning essence, as the Father. So while man is made in the image of God—God's essence remains fundamentally unknown to man. That's not the case with Christ, and His relationship to the Father.

Begetting deals with essence; something created lacks the essence of its creator, even if that thing has the image, like man being created in the image of God.

There’s also the necessity of differentiating between the human father begetting a son, and the Father begetting the Son. The human analogy is a good analogy, but it leaves something out, as all analogies do. A human son does not have the same essence as his human father, in the way that the Son has the same essence as the Father. But the human son does kind of have his father’s essence.

So in a sense, the human father both begets and ‘creates’ his son. But the Father only begets the Son—here we are thinking of monogenēs—and we are using the English word ‘begets’ as an analogy when speaking of God.

Because in the Trinity we’re dealing purely with essence, and not creating in the image, both of which happen in the human example. Ultimately, the difference is that begetting is about transference of essence and creating is about making in the image.

Essence is a closer identity claim between two things than image is. In the Trinity, the transference of essence is a 1:1 identity claim; monogenēs. Image is a much further apart identity claim. "Originates from," might be a good way to describe creating in the image of. While essence might be described as "is the same thing."

Here, the human father and human son analogy breaks down. Because a human father is not in a 1:1 identity relationship with his son. Even though that analogy is still useful, because in the created world we don't really see things with a 1:1 identity. But in the Trinity there is a 1:1 identity. And the human father is still closer to his son, in terms of identity, than a man would be to a cross he creates. Even though, both of these are creations; although the human son is also begotten.

The Father eternally begets a 1:1 identity in His Son. But something created lacks that identical identity.

Although—the following are faith claims—the Father is not the Son and the Son is not the Father. The Trinity is a mystery, but if we’re going to try and talk about it with reason, we could say that the Trinity is one essence in three Persons.

So the eternal begetting of the Son, from the Father, is a 1:1 identity claim—but it’s also not a 1:1 identity claim. The Son is and is not the Father, in certain senses—as the Holy Trinity is a faith claim beyond reason. The claim doesn’t make sense in strict mathematical logic. But it does make sense in practice. Love also does not make sense in strict mathematical logic.

Jesus Christ speaks very mysteriously in the Gospel of John, whenever He mentions the identity relationship between Himself and the Father. “I and the Father are one” (John 10:30). “I am in the Father and the Father is in Me” (John 14:11). But Christ also defers to the Father as if the Father is different from the Son. “My Father is greater than I” (John 14:28).

In the Gospel of Mark, after Christ is called good, He says that “No one is good, only God” (Mark 10:8). These last two examples could be partly because Christ is speaking as a human being—speaking as the Son who takes on the limitation of being human, and who is therefore lesser than the Father—but it could also be because the Persons of the Trinity seem to always want to defer to each other’s greatness, because God is love.

So what makes something begotten vs. created?

The difference is about identity. And essence vs. lack of essence. Begotten is a closer identity relationship because of essence. While creating—which is necessarily always in the image of something, even if it is just the image of a man’s idea of a cross—does not carry essence through to the created thing.

A human man both begets and creates his son. The identity relationship in creating, is always less close than in begetting. And the identity claim with the Father eternally begetting the Son, is both a 1:1 identity claim about essence—and not 1:1, but still about essence.

Yet if a person rejects the existence of essence, there is not much I can do. Although, that also means that such a person does not believe in ‘universals,’ meaning categories such as ‘cows.’ That person only believes in individual cows. Again, there is only so much I can do.

Man is created in God’s image, but lacks God’s essence. Christ is eternally begotten, and has the Father’s essence. That’s why the Nicaean Creed states that Christ is “True God from True God.” He is “eternally begotten,” not created.

In terms of the objection that Christ, because he is human, is created—that is dealt with in the original article. That objection was the Arian heresy.

Saint Thalassios the Libyan, in the Orthodox Philokalia, notes how we can think about “the essence of the Holy Trinity, but [those ideas] do not refer to the essence itself. For the principles of the essence cannot be known by the intellect or expressed in words; they are known only to the Holy Trinity.

“Just as the single essence of the Godhead is said to exist in three Persons, so the Holy Trinity is confessed to have one essence.”

All of that is why Saint Gregory Palamas, and Saint Thomas Aquinas—although with different words and different categories—seem to be in agreement that God’s energies are how He acts in the world, while His essence remains fundamentally unknowable to man.

Dan Sherven is the author of four books, including the number one bestseller Classified: Off the Beat ‘N Path and Uncreated Light. Sherven is also an award-winning journalist, writing for several publications. Find Sherven’s work.

Dan, thanks for this follow-up article. The tension between begetting and creating is another instance of the attempt to reconcile the age-old question of the one and the many. It also is one of many theological by-products of dualistic theology rooted in the acceptance of ontological separation between God and man (and all that is). If we accept dualism, begetting vs creating is necessary. But it isn't necessarily so.

There's a bigger, more fundamental question we must face: Is reality dual or non-dual? Is there really an infinite, ontological gap between God and man and the entire cosmos? Perhaps we've been too quick to say yes. Perhaps we should further investigate the nature of reality.

Like the human father and son, you rightfully admit that "the Father is not the Son and the Son is not the Father." However, unlike the Father and the Son's unity of essence, you claim that "a human son does not have the same essence as his human father" but only "kind of." How can there be a difference in something that is essential? It would cease to be essential, thereby making the father and son essentially different. Here again, we see the tension of the one and the many. We struggle to find coherent words to express how it is that God is "one essence in three Persons," just as mankind is somehow one, but many. The issue again is our acceptance of the duality of reality.

I submit that the solution has always been staring us in the face. Reality only appears dual. Reality is in fact non-dual. There is no separation between God and the manifest cosmos. There is no essential, substantial, infinite ontological separation between God and man and all that is. Just as God is described as "one essence in three Persons," so too is the entire cosmos an infinite multitude, but one in essence.

It's claimed that "begetting is about transference of essence and creating is about making in the image." Yet Christ is said to be the image of God. Is Christ then not also created? Furthermore, if begetting transfers essence, then we must also say that the Holy Spirit is begotten of the Father - yet we do not. Begetting would no longer distinguish the Son from the Spirit.

I submit that our understanding of the Trinity is in need of refinement. Begetting and creating are attempts at describing the one and the many, respectively. Let us not divorce our understanding of them from the persons of the Trinity, but rather expand our understanding of Christ and the Holy Spirit. Begottenness is associated with the Son. Creating is the activity of the Holy Spirit. It is specifically through the procession of the divine energies of the Holy Spirit that God is made manifest (i.e., begotten). With a non-dual vision of reality, we can see that the entire cosmos is Christic. The immanent, manifest universe is eternally begotten of the transcendent Father as the created image of God by the procession of the divine energies of the Holy Spirit. This non-dual vision of reality is both begotten and created, one in essence and yet uniquely many.